Share this article

More businesses are understanding the competitive advantage of integrating Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG), or sustainable practice, into their core business strategies.

While this can produce strong positive impact by aligning profit with environmental and stakeholder interests, according to the annual report The Year Ahead: Global Disputes Forecast 2022, we’re also seeing a sharp increase in ESG-related risk across APAC with disputes from greenwashing, social washing, and climate change at the helm.

The tide is turning on businesses claiming sustainable practices, and stakeholders, now armed with an understanding of ESG, are demanding organisations build robust, future-focused ESG strategies.

Making Sense of ESG

Globally, ESG as a concept has become the best way for many different interest groups to approach the vast concept of sustainability together. Yet even with this shared language, there are fundamentally different ways that ESG is used as a tool. For example, the finance industry is buzzing with the concept as the largest investment management firms like BlackRock allocate more and more trillions of dollars using ESG metrics as selection criteria, a pool of money that they claim accounts for more than a third of total global assets and climbing fast.[1]

On the other hand, lawyers, compliance officers, and corporate risk professionals see ESG as an emerging risk. Climate change disputes, greenwashing and social washing litigation, discrimination, and modern slavery compliance obligations are all soaring, according to Baker McKenzie’s latest Global Disputes Forecast.[2] ESG offers them a way to organise their defense against a broad field of new and dire threats.

But I prefer to think about ESG in broader terms; it’s a tool to reorganise capitalism so that it works better and will keep working indefinitely without exploiting people and destroying the planet.

Boards, executives, and your average conscious citizen see ESG this way, too, as a practical method for designing and actioning more sustainable ways of doing business. It should enable broad improvements like continued access to finance, competitive advantage, reduced risk, and the ability to meet fast-changing stakeholder demand.

Understanding concepts for designing and implementing an ESG strategy, will save companies making late-game corrections right before a sustainability report or activity roadmap goes public.

Three Concepts for a robust ESG strategy

1. Inward and outward impact – consider both sides of the ESG impact coin, or you miss half the picture

To develop a comprehensive ESG strategy, an organisation must consider both directions of ESG impact (see Figure 1 below). The most intuitive direction (for companies) is inward impact which focuses on the effect of sustainability-related risks and opportunities on an entity’s enterprise value; for example, climate change increasingly causing supply chain disruptions of essential materials.

Figure 1: Two directions of ESG impact and their respective sustainability standards

The other direction of ESG impact is an organisation’s outward effect on the economy, environment, and stakeholders. This should be broad and include an entity’s potential and indirect impacts through supply chains or business relationships. For example, the way an organisation uses and disposes of water may significantly affect the surrounding community.

Sustainability strategies and disclosures should factor in both directions of ESG impact.

2. No company can address every issue – stay focused on your main impact

There is an almost endless amount of ESG topics, indicators, and targets that are important for the planet and its people, making it easy for organisations to get lost amidst their own good intentions. The trick is staying focused on the few issues more relevant for your organisation.

To achieve that focus, each organisation should start their ESG strategy with a ‘materiality assessment’ to identify and prioritise their most significant impacts. Best practice methods for conducting these assessments are detailed by the UN, SASB, and GRI and should integrate stakeholder priorities and sentiment.

I suggest arriving at five to seven material ESG topics, which is hard to do. It can seem unnatural to omit issues that matter to global sustainability, but one organisation can’t do everything. Selecting all ESG issues that you support can ultimately dilute your ESG strategy and slide towards greenwashing and social washing.

After determining your most material topics, wrap your ESG strategy and disclosures around them – they become your sustainability framework that indicators, targets, and activities flow from.

3. Re-wire your ESG-thinking to be stakeholder-centric

While tempting to think that the main character of ESG is your organisation, it’s actually the planet, people, and the ecological and economic systems that people rely upon. Organisations have to re-wire their thinking to be stakeholder-centred, particularly when considering the half of ESG that looks at outward impact.

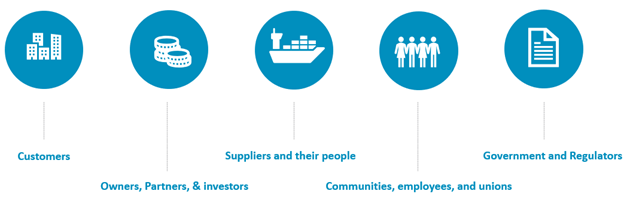

From the start it’s worth defining your stakeholder ecosystem and keeping this broad array of characters front of mind while developing an ESG strategy. Your organisation probably has more stakeholders than you think. Consider all people and groups that have interests affected by your organisation’s activities.

Figure Two: Example Stakeholder Identification for a medium-sized organisation

Organisations that determine the sustainability priorities of this diverse array of stakeholders are well placed to design and implement an impactful ESG strategy that meets or exceeds expectations and stacks up against all the green noise currently out there.

Further reading Environmental, Social, Governance | Why is the S in ESG so hard?

Article originally published in Forbes